On January 13, 2020, the U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury), on behalf of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS or the Committee), issued two sets of final regulations implementing the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA) — one for certain covered real estate transactions and one for all other covered transactions. These final regulations follow proposed regulations that the Treasury published on September 17, 2019, which were open to public comment until October 17, 2019. Although the Committee made a few noteworthy changes in response to public comments, the final regulations are substantially similar to the draft ones.

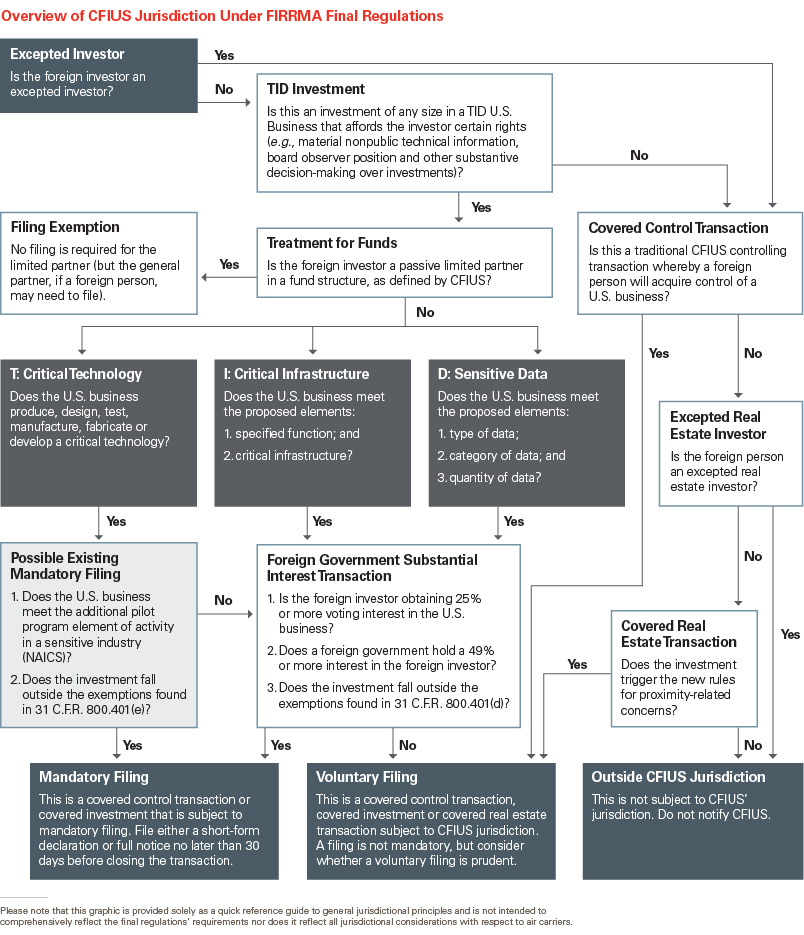

Consistent with our analysis of the draft regulations, the Treasury’s FIRRMA regulations — now in their final form — largely adopted many pre-FIRRMA CFIUS trends, standards and practices while adding some new features, such as expanded jurisdiction over non-controlling investments and real estate transactions, as well as mandatory filings for certain deals. The regulations, like the FIRRMA itself, are a response to three concerns: (i) that foreign acquisitions of early-stage U.S. technology companies jeopardize the United States’ technological advantage, particularly in emerging and foundational technologies whose importance to national security may not yet be apparent; (ii) that foreign actors, particularly China, can use acquisitions of U.S. companies possessing significant amounts of sensitive personal data as an easy, legal form of bulk intelligence collection on U.S. citizens; and (iii) that the ability to acquire real estate, which on its own was not a covered transaction pre-FIRRMA, provides foreign actors an opportunity to gain physical proximity to sensitive U.S. government facilities.

The final regulations, which become effective on February 13, 2020, implement almost all of the FIRRMA, and provide clarity on the Treasury’s interpretation of covered minority investments, covered real estate transactions, excepted investors and mandatory filings for foreign government-related investments. However, some issues remain open. Future planned rulemaking is required to address, for example, changes to mandatory filings for critical technologies, the definition of “principal place of business” and the CFIUS filing fees.

Even with the added clarity that the FIRRMA regulations provide in many contexts, dealmakers must still approach CFIUS decision-making on a case-by-case basis depending on the risks raised by the particular buyers and the sensitivities raised by particular assets, weighing considerations such as deal certainty, risk and timing. Below we highlight key provisions of the FIRRMA regulations that will impact clients as they consider future transactions.

Mandatory Filings Are a Permanent Feature of the FIRRMA Regime

In a change to CFIUS’s long-standing history as a purely voluntary process, the FIRRMA regulations require parties to submit a declaration, i.e., a shortened version of the standard CFIUS notice, in two types of transactions: certain foreign government-related transactions and certain “critical technology” investments. The regulations provide the required contents for a declaration, which represent a somewhat shorter list of the requirements for a notice, and specify that the review period for a declaration is 30 calendar days (compared to the potential 90 calendar days for a traditional notice review and investigation). Although the declaration ostensibly offers a more streamlined process, parties in mandatory filing cases should consider whether to file a traditional notice in lieu of a declaration (this calculus may differ in voluntary declaration scenarios, discussed further below).

First, parties must file a declaration for any covered transaction that results in a foreign government having a “substantial interest” in a Technology, Infrastructure, or Data (TID) U.S. Business. A substantial interest arises when a foreign person obtains a 25 percent or greater voting interest, directly or indirectly, in a U.S. business if a foreign government in turn holds a 49 percent or greater voting interest, directly or indirectly, in the foreign person. Importantly, although the draft regulations stated that a fund where 49 percent or more of the voting interest of the limited Skadden Partnersis held by a foreign government would meet the second prong of the substantial interest test, the final rules now instead provide that the foreign government’s 49 percent interest must be in the general partner in order to trigger a mandatory filing.

Second, parties must file a declaration for certain noncontrolling or controlling investments in U.S. businesses that produce, design, test, manufacture, fabricate or develop critical technology in 27 enumerated industries. This matches the CFIUS “pilot program” initiated by the Committee in October 2018 and discussed in our previous alert. The U.S. Department of Commerce (Commerce) has yet to specifically identify the emerging or foundational technologies that will form a significant part of critical technologies pursuant to its ECRA mandate, but is taking affirmative steps toward doing so, as detailed in our recent publication “Commerce Department Will Move Forward With More Stringent Export Controls for Certain Emerging Technologies.”

By its nature, the pilot program was experimental and the Treasury, in its September 2019 draft regulations implementing FIRRMA, indicated that it would address the status of the pilot program. The Treasury did so in its final rules, but essentially delayed substantive changes to the program until a later date. As a consequence, the pilot program in its current form remains in effect through February 12, 2020. Beginning February 13, 2020, the pilot program will continue to remain in effect but operate within Part 800, rather than Part 801, of the CFIUS regulations. According to the final rule, the Treasury anticipates issuing a separate notice of proposed rulemaking that would effectively eliminate the association between “critical technologies” and the 27 industries previously identified as sensitive. Instead the mandatory filing requirement would be triggered by export licensing requirements alone.

The shift away from North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes presumably reflects the Treasury’s concerns with the inherent ambiguities in basing the jurisdictional scope of a mandatory filing requirement on self-designated industry classifications. From a purely national-security standpoint, although the 27 industries identified in the pilot program represent a wide swath of those that would likely raise national security concerns, the justification for treating two companies making the same critical technology differently based on self-assigned NAICS code differences was always suspect. However, how replacing NAICS Codes with an export licensing prong will impact the scope of transactions for which mandatory filings would be required remains to be seen. For example, if the issue becomes whether an export license is required for a certain technology to be exported to the home country of the investor, for certain technologies certain countries may be favored over others and the pilot program may not capture a substantial number of new transactions. On the other hand, because many critical technologies would require licenses for export to most countries, opening the program to all industries could materially expand the scope of mandatory filing.

Nonetheless, we expect the Treasury will continue to scrutinize and prioritize transactions involving businesses that operate in sensitive sectors despite possible changes to the mandatory filing criteria. For most foreign investors considering transactions in these spaces, a voluntary filing will remain the norm.

In a welcome development, the final regulations do provide some exceptions1 to mandatory filing requirements, notably including:

- Investments by foreign entities operating under a valid facility security clearance and subject to mitigation agreements with the Defense Security and Counterintelligence Agency (DCSA)2 to address foreign ownership, control or influence (FOCI);

- Investments by funds controlled and managed exclusively by U.S. nationals;

- Investments where the U.S. business is a TID U.S. business solely because it produces, designs, tests, manufactures, fabricates or develops one or more critical technologies that is eligible for export, reexport or transfer (in country) pursuant to License Exception ENC (for encryption commodities, software, and technology) of the Export Administration Regulations; and

- Investments by “excepted investors,” a new category of investors described further below.

The very specific exception for investments involving License Exception ENC — which covers those involving most commercial and dual-use encryption items — will be especially welcome relief to many early-stage technology companies and investors. Nascent companies engaging in software development and Software-as-a-Service providers will now have clarity that the encryption controls used in their products and services will not, on their own, create a mandatory filing requirement.

Although transactions falling into one of these categories are not subject to mandatory filing, other than for non-controlling transactions by excepted investors, these transactions remain subject to the CFIUS’s jurisdiction. In other words foreign investors must still consider whether a voluntary filing of the transaction is warranted.

Despite the relatively limited scope of these exceptions with regard to the CFIUS’s formal jurisdiction, they may also be a useful signal regarding the Committee’s general view of risk presented by certain entities. For example, by providing that a company subject to a FOCI agreement with DCSA is not subject to mandatory filing for a critical technology investment, the Committee may be signaling more broadly that it views such an entity as low-risk. This means that, at least for transactions involving less sensitive assets, the FOCI-mitigated company may expect a lighter touch from the CFIUS. Parties still may consider using the CFIUS process and statutory time frame as a lever to move the DCSA process forward expeditiously.

Limited Application of Excepted Investor Status

In what many saw as a significant compromise to the FIRRMA’s expanded jurisdiction over non-controlling investments and certain real estate transactions, and in response to various calls for country-based approaches to the CFIUS regulations, FIRRMA requires the Committee to specify criteria for limiting the application of its expanded jurisdiction to certain categories of foreign persons. The FIRRMA regulations implement this limitation through the creation of “excepted investors,” i.e., investors having sufficiently strong ties to certain “excepted foreign states.” The final rules have borne out our assessment, expressed with regard to the original “excepted investor” scope proposed in the draft regulations, that the exception is unlikely to have a significant effect, or any effect at all, for the vast majority of foreign investors.

Only three countries that share extremely close intelligence and foreign-investment-review relationships with the United States — Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom — are excepted foreign states under the FIRRMA regulations. The regulations provide a mechanism for other countries to be added to the list, but we do not expect significant or rapid expansion of the excepted countries list. Although the final rules lower the bar somewhat to meet “excepted investor” status, the threshold remains high, potentially excluding a number of investors originating in the excepted countries.3 Accordingly, relatively few entities will qualify as excepted investors.

Moreover, the payoff for qualifying as an excepted investor is relatively small. For excepted investors, the FIRRMA regulations restore the pre-FIRRMA jurisdictional status quo. Excepted investors are not subject to the CFIUS’s expanded jurisdiction for non-controlling investments or covered real estate transactions, or to mandatory filing requirements, but they remain subject to the CFIUS’s “traditional” jurisdiction for transactions that would result in their control of a U.S. business. As noted in the review above of mandatory filings, although the jurisdictional application of this exception is somewhat limited, it also undoubtedly signals that CFIUS generally views investors from these countries as presenting a low threat to U.S. national security. Excepted investors will still want to carefully consider whether to voluntarily file controlling transactions (including through the new process for voluntary declarations), particularly when acquiring potentially sensitive assets.

Potential Efficiencies From the Voluntary Declaration Process

A potential benefit of the FIRRMA regulations that applies more broadly than its jurisdictional exceptions is the option to file a declaration, i.e., a short-form notice, for any covered transaction or covered real estate transaction. At least for acquirers likely to be viewed as a relatively low threat that are acquiring assets with limited or no national security implications, the declaration provides an opportunity to obtain a CFIUS safe harbor through a more streamlined and quicker process. The declaration evaluation phase lasts only 30 days compared to the 45-day notice review period, which can extend a further 45 days if the Committee moves the case to investigation. We expect that for many low-risk or repeat filers, the declaration process will not only provide a shorter government evaluation period, but also allow for expedited preparation of the declaration itself, shaving weeks off of the overall timeline.

For acquirers that may present a higher risk to national security or that have not previously been through the CFIUS approval process, or for any acquirer investing in or acquiring a sensitive asset, however, we expect that filing a full CFIUS notice instead of a declaration will remain advisable. Given the depth and breadth of national security concerns, the Committee must consider in such cases that a 30-day declaration evaluation period will likely not allow it enough time to fully analyze potential risk and provide clearance. We expect that, in time, the voluntary declaration process will become a tool for the Committee to triage matters and focus its attention on truly sensitive transactions, while allowing trusted parties or straightforward transactions to have regulatory certainty in a shortened timeframe. However, the shortened review period and limited information provided in declarations also make reaching a determination on a case more difficult for the Committee, meaning that parties with more complex transactions will want to consider foregoing a declaration and filing a notice.

Real Estate Regulations Do Not Preclude Other CFIUS Jurisdiction

Pre-FIRRMA, the CFIUS held jurisdiction over transactions involving a “U.S. business,” i.e., an entity engaged in interstate commerce in the United States. The FIRRMA expanded the CFIUS’s jurisdiction to review purchases, leases and concessions of real estate by foreign persons, including Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) irrespective of whether such transaction involves a U.S. business. With little modification from the draft regulations, the final regulations focus on vulnerabilities exposed by real estate proximities to airports and maritime ports as well as to military installations or other sensitive U.S. government facilities or properties.

The Committee anticipates providing a web-based tool for the public to better understand the geographic coverage of the final regulations. Investors should remain cognizant, however, that the Committee’s expanded jurisdiction over real estate transactions does not subsume the Committee’s preexisting jurisdiction over transactions that could result in foreign control or certain non-controlling investments by a foreign person in an entity engaged in interstate commerce that also owns or leases real estate. The Committee’s comments to the FIRRMA regulations make clear that proximity to sensitive facilities (including some not listed in the regulations) will continue to play an important role in the Committee’s national security risk analysis for covered control transactions and covered non-controlling investments. Thus, the real estate regulations do not provide relief for real estate-related investments previously covered by the CFIUS’s jurisdiction but instead expand its jurisdiction to new types of real estate transactions that do not constitute a U.S. business.

Data Remains a Central National Security Concern

Unsurprisingly, CFIUS maintained its stance on the national security importance of personal data. A U.S. business collecting or maintaining sensitive data — or having the strategic intent to collect or maintain such data — on one million or more persons will still qualify as a TID U.S. Business.

The final regulations provide limited narrowing of this relatively low threshold from what was originally proposed in the September 2019 draft. For example, the final regulations provide that a U.S. business that has collected sensitive data on over one million persons in the past year may demonstrate that it does not and will not have the capability to maintain or collect sensitive information on over one million persons as of the closing of a transaction in question. The final regulations also provide that data used for analyzing or determining financial distress or hardship is now limited to "financial" data. The scope of genetic information has also narrowed from the original proposal to only include the results of an individual's genetic tests with the added exception of data derived from databases maintained by the U.S. government and routinely provided to private parties for research purposes.

Despite these narrowing efforts, the scope of sensitive data remains quite broad. Possessing data on one million or more persons is no longer a sizable figure for many businesses. Furthermore, the FIRRMA regulations note several scenarios where a U.S. business may qualify as a TID U.S. Business without possessing sensitive data on one million or more persons, including cases where the total sum of different types of data adds up to more than one million persons. Also of interest to early-stage investors, the regulations make clear that a strategic intent to collect or maintain information on over one million persons (coupled with concrete steps taken to achieve this goal) is sufficient to trigger jurisdiction. Ultimately, given this low threshold to prompt a CFIUS review, parties should generally focus their decision-making regarding whether to file more on the nature of a U.S. business’s data than how much of that data the company possesses or is likely to possess in the future.

Providing Greater Clarity Through Examples

The Treasury’s addition to the final guidance of examples outlining the Committee’s interpretation of its own rules provide further helpful instruction. The examples often come directly from specific transactions that the Committee has reviewed over the past few years, largely codifying its evolving practices. Notable examples include providing clarity on several key terms:

- “Material Nonpublic Technical Information” — The Committee added color to its interpretation of “material nonpublic technical information,” a source of considerable consternation for parties since the implementation of the pilot program in October 2018. In its example, the CFIUS states notifications of certain developmental milestones achieved (without accompanying technical details) do not constitute material nonpublic technical information necessary to design, fabricate, develop, test, produce or manufacture a critical technology.

- “U.S. Business” — The final regulations provide an example in which a foreign business remotely servicing customers in the United States did not meet the definition of a “U.S. business” subject to the CFIUS’s jurisdiction. Although helpful insight, investors should remain aware that the Committee reviews each transaction on its specific set of facts and circumstances and another transaction, although similar in structure, may fall within the Committee’s purview.

- “Incremental Investments” — The final regulations provide further clarity on the treatment of incremental investments, confirming that investments made by the same foreign person in the same U.S. business after the Committee has previously cleared a transaction by that foreign person as a controlling investment will not be considered new covered transactions subject to review. However, if a subsequent investment would result in the foreign person obtaining control of the target (i.e., the Committee previously cleared the transaction as a covered investment, rather than a covered controlling transaction), that would be a new covered transaction, as would a subsequent investment by an affiliated entity (i.e., an entity that shares the same parent as the foreign person).

Clarifications for Private Equity & Venture Capital

In the one element of the January 13th publication that is not a final rule, the Committee proposed a definition of “principal place of business,” a previously undefined term that is a key factor in deciding whether an entity is a foreign entity. The proposed definition essentially follows the “nerve center” test used by federal courts in evaluating federal diversity jurisdiction. Under the definition, an entity’s principal place of business is “the primary location where an entity’s management directs, controls, or coordinates an entity’s activities, or, in the case of an investment fund, where the fund’s activities and investments are primarily directed, controlled, or coordinated by or on behalf of the general partner, managing member, or equivalent.” This definition is particularly useful for clarifying that the Committee will look past decisions to domicile an entity in a particular jurisdiction for tax or other legal reasons where that domicile is not the “nerve center” of the entity.

In further fine-tuning of the definitions, the final regulations add “the general partner, managing member, or equivalent” to the definition of “parent.” The Committee received a number of public comments regarding the application of certain provisions of the regulations to funds and other entities with multiple layers of ownership and governance. For the Committee, this ensures that entities with the ultimate decision-making power in a fund are appropriately evaluated as entities exercising such control, for example, when considering whether or not a foreign person meets the definition of an “excepted investor.”

Lastly, since the pilot program's implementation many have questioned the applicability of the mandatory filing requirement to a fund and its limited partners. As described above, the final regulations provide an exemption for investment funds managed by general Skadden Partnerswho are controlled and managed by U.S. nationals. The regulations clarify, however, that a limited partner in a fund could have a filing obligation separate and apart from that of the general partner if the limited partner is afforded certain rights. If a limited partner, for example, is granted board membership or observer rights, involvement in substantive decision-making, or access to material nonpublic technical information of a critical technology U.S. business, the limited partner may be subject to its own mandatory filing even if the fund itself is not. Dealmakers will need to remain vigilant when negotiating rights granted to limited Skadden Partnersin sensitive technology transactions to avoid potentially hefty fines for a failure to file in a mandatory scenario.

Key Takeaways

- Mandatory filings are here to stay — and the final regulations fully implement the CFIUS’s authority on this front, now capturing certain foreign-government-related transactions.

- Parties must now consider voluntary filings for a certain non-controlling transactions in a broad range of TID U.S. Businesses.

- The public still awaits Commerce’s definitions of critical and foundational technologies, which will provide further clarity in understanding potential CFIUS concerns that may need to be addressed at the outset of a transaction.

- The bar to qualify as an “excepted investor” remains high and the benefits are limited.

- The final real estate regulations do not limit the Committee’s existing jurisdiction to review controlling transactions that involve real estate — and instead will capture a larger segment of transactions in the real estate space.

- Fund Managers should ensure that their fund documents do not provide limited Skadden Partnerswith significant governance rights over the fund’s operations and appropriately limit access to material nonpublic information — which does not include milestone information.

_______________

1 Certain exceptions apply to only one category of mandatory filings (either critical technology mandatory filings or substantial government interest mandatory filings).

2 Formerly the Defense Security Service (DSS).

3 Investors from these jurisdictions will not be required to file mandatory declarations for investments in critical technology or substantial interest transactions if they meet certain criteria, including a minimum excepted ownership threshold (all investors above 10% are of U.S. or excepted nationality) and no more than 25% board membership by foreign nationals of foreign states that are not excepted foreign states that are not excepted foreign states. Importantly, the Committee clarifies that an excepted investor must meet the criterion at each level of the ownership chain; ultimate parent compliance is not sufficient. This interpretation is consistent with similar regulatory policies, including those implemented by the Department of State’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls.

This memorandum is provided by Grand Park Law Group, A.P.C. LLP and its affiliates for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended and should not be construed as legal advice. This memorandum is considered advertising under applicable state laws.