On September 17, 2019, the Department of the Treasury, on behalf of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS or Committee), issued two sets of proposed regulations seeking to further implement the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA). These draft regulations — one for certain covered real estate transactions and one for all other covered transactions — answer many questions about how CFIUS intends to exercise its FIRRMA authorities but, as described below, also leave some matters to be addressed in the future.

The draft regulations are not immediately effective. Their release begins a 30-day public review and comment period that will expire on October 17, 2019. Only after Treasury considers submitted comments and reissues the final regulations with any changes will they take effect, likely early next year before FIRRMA’s statutory deadline of February 13, 2020.

In issuing the draft regulations, CFIUS largely retained — with some elaboration — pre-FIRRMA standards and practices. Although the draft regulations’ new provisions include some potentially significant changes to the Committee’s operations and jurisdiction, in most ways they represent the codification of trends in CFIUS practice that preceded FIRRMA. Specifically, those trends were the driving factors behind FIRRMA: (i) concerns over foreign access to data about U.S. citizens, (ii) concerns over foreign access to early-stage U.S. technology companies, and (iii) concerns over the ability of foreign persons to gain proximity to sensitive sites through real estate transactions. Below, we provide an overview of the key provisions in the draft regulations along with takeaways for clients.

Although the draft regulations’ new provisions include some potentially significant changes to the Committee’s operations and jurisdiction, in most ways they represent the codification of trends in CFIUS practice that preceded FIRRMA.

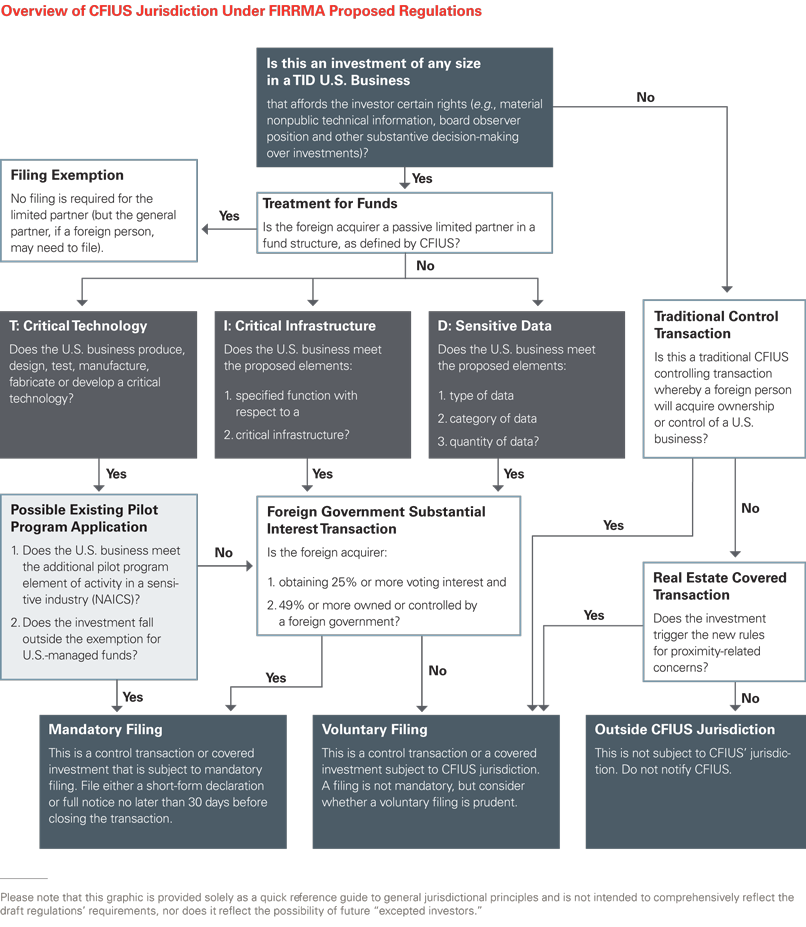

See the chart below for an overview of CFIUS jurisdiction under the proposed regulations.

Expanded Jurisdiction Over Investments in US Technology, Infrastructure and Data Businesses

One of FIRRMA’s more significant changes was to expand the Committee’s jurisdiction to some noncontrolling investments. Historically, a transaction had to result in a foreign person gaining “control” of a U.S. business for CFIUS to have jurisdiction and, although CFIUS interpreted “control” broadly,1 the definition had limits and permitted some forms of nonpassive investment to fall outside the Committee’s jurisdiction. At least for those U.S. businesses most likely to raise U.S. national security considerations, FIRRMA closed this perceived gap.

Specifically, for U.S. businesses involved in critical technology, critical infrastructure, or the collection or maintenance of sensitive data about U.S. citizens, FIRRMA expanded the Committee’s jurisdiction to include noncontrolling investments if accompanied by certain rights. The draft regulations provide necessary elaboration on FIRRMA’s broad definitions, thus clarifying CFIUS’ jurisdictional scope over these noncontrolling covered investments.

Under the draft regulations, a noncontrolling investment is a covered investment if it satisfies two prongs:

(i) it involves a U.S. business in certain industries; and

(ii) it affords the foreign person certain rights.

First Prong: Covered US Businesses

The Committee’s expanded jurisdiction over noncontrolling investments applies only to investments in a subset of U.S. businesses referred to in the draft regulations as technology, infrastructure or data U.S. businesses (TID U.S. Businesses).2

Technology US Businesses

U.S. businesses that produce, design, test, manufacture, fabricate, or develop one or more critical technologies — as defined by FIRRMA3 — constitute the first category of TID U.S. Businesses. The most significant development with regard to critical technologies is not these draft regulations but the regulations that the Department of Commerce will issue to implement the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 (ECRA). ECRA, a companion to FIRRMA, tasked Commerce with adding more stringent controls on emerging and foundational technologies to protect national security interests.4 On November 19, 2018, Commerce released an advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM) identifying certain representative categories of emerging technologies that could be captured under final ECRA regulations, but it has not released any new controls to date. During an advisory committee meeting on September 17, 2019, Commerce estimated that at least “some” emerging technologies will be identified in proposed regulations to be published by the end of the 2019 calendar year, and an ANPRM identifying possible categories of foundational technologies will be released “relatively soon.”

Any technologies identified by Commerce as emerging or foundational technologies will, by definition, be CFIUS critical technologies and thus be subject to all of the relevant requirements under the proposed regulations. Thus, the true scope of this aspect of FIRRMA remains uncertain pending Commerce’s reforms.

Infrastructure US Businesses

U.S. businesses that own, operate, manufacture, supply or service critical infrastructure, defined as those “systems and assets, whether physical or virtual, so vital to the United States that the incapacity or destruction of such systems or assets would have a debilitating impact on national security,” constitute the second category of TID U.S. Businesses. But under the draft regulations, only a U.S. business that performs one of the specified functions with respect to a correlating covered infrastructure qualifies as a TID U.S. business. A list of covered investment critical infrastructure and associated functions are set forth in Columns 1 and 2, respectively, of Appendix A to Part 800.

Examples of covered investment critical infrastructure include certain internet protocol networks; telecommunications services; internet exchange points; submarine cable systems and landing facilities; certain satellites and satellite systems; facilities manufacturing special metals and chemical weapons antidotes; bulk-power system facilities; industrial control systems; financial market utilities, rail lines; and certain interstate oil and gas pipelines.

As a general matter, the draft regulations track with CFIUS’ past practice, but the detail provided in the regulations will provide significantly greater clarity to investors in these sectors. For example, with regard to satellites, the regulations provide that only U.S. businesses owning or operating satellites providing services directly to the Department of Defense or any of its components are covered. Thus, although some set of investments may be more likely to garner CFIUS’ attention, this cost is at least somewhat offset by the increased transparency for critical infrastructure operators and investors.

Data US Businesses

U.S. businesses that maintain or collect, directly or indirectly, sensitive personal data of U.S. citizens constitute the third category of TID U.S. Businesses. Recognizing that virtually every U.S. business possesses at least some personal data of U.S. citizens, CFIUS provides several factors and definitions ostensibly designed to narrow its application, but all of which highlight the breadth of the challenge for CFIUS, businesses and investors. In sum, the draft regulations will affect a wide range of companies that may not have traditionally considered themselves of interest to U.S. national security.

The parameters for what constitutes sensitive personal data are as follows:

- Sensitive personal data must be “identifiable data,” meaning that it “can be used to distinguish or trace an individual’s identity, including without limitation through the use of any personal identifier.” Aggregated or anonymized data is not covered if a party to the transaction lacks the ability to disaggregate or de-anonymize the data. Encrypted data may also be excluded if the U.S. business does not have the ability to de-crypt the data or trace an individual's identity through the data.

- The identifiable data must fall into one of the categories enumerated in the draft regulations, including:

- information that could be used to determine financial distress or hardship (which does not include consumer purchase information);

- data from a consumer report, subject to certain exceptions;

- insurance application information;

- health information;

- nonpublic electronic communications such as email or text messaging;

- biometric enrollment data;

- information about U.S. government security clearances and applications for such clearances;

- genetic information, such as genetic test results; and

- geolocation data, regardless of the method of collection (e.g., mobile app, vehicle GPS, wearable).

- The U.S. business must have (i) data maintained or collected on over 1 million individuals, (ii) a demonstrated objective to maintain or collect data on over 1 million individuals, and the data is an integrated part of the business’ primary product or service, or (iii) any amount of data if the business targets or tailors products to U.S. national security agencies or their personnel. It is important to note that these data counts are not limited to U.S. citizens, which further lowers the bar, and do not apply to genetic information.

- The regulations exempt data concerning one’s own employees or publicly available information.

Second Prong: Covered Rights

To be a covered investment, the noncontrolling investment in a TID U.S. business must afford the foreign person at least one of the following:

- Access to material nonpublic technical information, which encompasses information that is not available in the public domain and (i) provides knowledge, know-how or understanding of the design, location or operation of critical infrastructure, including without limitation vulnerability information such as that related to physical security or cybersecurity; or (ii) is necessary to design, fabricate, develop, test, produce or manufacture a critical technology, including without limitation processes, techniques or methods. Importantly, consistent with FIRRMA, the draft regulations provide that this does not include financial information regarding the performance of an entity.

- Membership or observer rights on the board of directors or equivalent governing body, or the right to nominate an individual to a position on the board of directors or equivalent governing body.

- Any involvement, other than through the voting of shares, in substantive decision-making regarding the use, development, acquisition, safekeeping or release of sensitive personal data of U.S. citizens; the use, development, acquisition or release of critical technologies; or the management, operation, manufacture or supply of critical infrastructure.

Mandatory Versus Voluntary Filings

Mandatory Filings

Another of FIRRMA’s more significant changes was the establishment of a mandatory filing regime. FIRRMA (i) authorizes CFIUS to mandate the filing of a declaration (i.e., a short-form notice) for certain transactions involving “critical technology” by any foreign person and (ii) requires CFIUS to mandate the filing of a declaration for certain transactions in which a foreign government, i.e., any government or body exercising governmental functions, has a “substantial interest.”

Critical Technology Pilot Program5

CFIUS implemented its authority to mandate filings for noncontrolling and controlling investments involving “critical technology” in 27 enumerated industries through a pilot program established on October 11, 2018. The draft regulations do not modify the program, which remains in place. They do, however, indicate that CFIUS will address the status of the program in its final rule due by February 20, 2020.

Foreign Government ‘Substantial Interest’ Transactions

Under the draft regulations, any covered transaction that results in a foreign government having a “substantial interest” in a TID U.S. Business will be subject to mandatory filing. CFIUS defines “substantial interest” as any situation where a foreign person obtains a 25 percent or greater voting interest, directly or indirectly, in a U.S. business if a foreign government in turn holds a 49 percent or greater voting interest, directly or indirectly, in the foreign person. In the case of a limited partnership, a foreign government will be considered to have a “substantial interest” if it either (i) holds 49 percent or more of the voting interest in the general partner or (ii) 49 percent or more of the voting interest of the limited partners. Parties will be required to submit mandatory filings 30 days prior to completing the relevant transaction.

Voluntary Filings

It is important to note that despite the new category of mandatory filings, the vast majority of the Committee’s jurisdiction — including with regard to the covered noncontrolling investments in many TID U.S. Businesses — remains subject only to a voluntary filing requirement.

To that end, the draft regulations do provide a new filing mechanism: a voluntary declaration. In voluntary filing scenarios, parties to a transaction will now have the opportunity to file a declaration (i.e., a short-form notice) instead of a full notice. Although we expect that voluntary filing of a full notice will still be warranted in many cases involving greater sensitivity or complexity, the option to file a voluntary declaration provides parties with increased flexibility to obtain a CFIUS review and determination on their transaction in a shorter time frame (i.e., 30 rather than 45 days).

Real Estate Transactions

As noted above, CFIUS issued a separate set of draft regulations specific to its expanded authority to review real estate transactions provided by FIRRMA. As CFIUS stated in the commentary to these regulations, prior to FIRRMA it could only review an acquisition of real estate if the acquisition was part of a transaction that could result in control by a foreign person of an entity engaged in interstate commerce in the United States. Under FIRRMA, the Committee’s jurisdiction now includes certain types of stand-alone real estate transactions involving the purchase or lease by, or a concession to, foreign investors that provides the foreign person three or more of the following property rights: to physical access; to exclude; to improve or develop; or to affix structures or objects.

The proposed regulations focus on two types of real estate vulnerabilities: (1) proximity to airports and maritime ports; and (2) proximity to military installations or other sensitive facilities or properties of the U.S. government. “Covered real estate” under the proposed regulations includes property that:

1. is, is located within or will function as part of an airport or maritime port (800.211(a)); or

2. is located within:

a. 1 mile of any military installation listed in a specified appendix to the regulations, including, for example, bases, arsenals, research laboratories and radar sites (800.211(b)(1));

b. 100 miles (and, to the extent applicable, no more than 12 nautical miles from the U.S. coastline) of any continental U.S. Army combat training centers, major range and test base activities, certain military ranges and joint forces training centers in certain states, all as listed in a specified appendix to the regulations (800.211(b)(2));

c. any county or other geographic area identified in connection with any active U.S. Air Force ballistic missile fields ((800.211(b)(3)); or

d. any part of a U.S. Navy off-shore range complex or off-shore operating areas as listed in an appendix to the regulations (800.211(b)(4)).

In all of the cases above with the exception of 800.211(a) and (b)(1), real estate within an urbanized area or urban cluster (as defined by the U.S. Census) is excepted, which should exempt most major metropolitan areas. The regulations also provide an exception for transactions involving certain commercial office space in multiunit buildings and the purchase, lease or concession of a single “housing unit,” including the fixtures and adjacent land incidental to use as a single housing unit. The regulations do not require filings for the real estate transactions described above; the process remains voluntary.

Importantly, the draft regulations do not limit the Committee’s jurisdiction to review other real estate-related transactions (e.g., acquisitions of real estate investment trusts, hotel chains) which could result in foreign control of a U.S. business or other covered investments. As noted above, CFIUS retains its ability to review any real estate transaction if the transaction involves the acquisition of a U.S. business by a foreign person and is otherwise a covered control transaction or covered investment and — historically — the Committee has interpreted the definition of U.S. business broadly to capture a wide range of transactions. Foreign acquirers will still need to consider whether to file with CFIUS voluntarily under the existing regime if the U.S. business encompasses real estate that presents other vulnerabilities, such as foreign access or proximity to sensitive tenants or technology.

Special Treatment for Certain Foreign Investors

In the lead-up to enacting FIRRMA, various constituencies advocated for different, country-based approaches to the CFIUS process. As enacted, FIRRMA directed CFIUS to specify criteria to limit the application of FIRRMA’s expanded jurisdiction to certain categories of foreign persons. In the draft regulations, CFIUS accomplishes this limitation by creating an exception to covered investments for certain foreign persons, to be defined as “excepted investors.”6 In short, CFIUS has begun the process of creating a list of friendly nations for which investors may receive special treatment for their TID U.S. Business investments.

An investor is excepted based on the combination of several criteria, including its ties to certain countries through place of formation, ownership, principal place of business; its previous history of compliance with CFIUS; and its compliance with certain other laws, orders and regulations such as export controls and sanctions laws. In turn, the investor must be associated with an “excepted foreign state.” The draft regulations do not identify these foreign states, but CFIUS identified the factors that it will use in creating such a list, including, notably, whether a foreign state has established a robust foreign investment review regime and is coordinating with the United States on investment security matters.

Despite the hopes of many foreign investors, these provisions are unlikely to have a significant impact (if any at all) for at least two reasons. First, even if “excepted,” an investor will not be exempt from CFIUS but rather will only be exempt from the relatively narrow class of mandatory filings; CFIUS’ jurisdiction over voluntary filings will remains unchanged for both excepted and nonexcepted investors. Second, CFIUS is likely to include only the United States’ closest allies on the list of “excepted foreign states” given the contemplated requirements. Finally, even for those investors lucky enough to qualify, given the draft regulations’ relatively complex methodology for recognizing excepted countries, we do not expect any exceptions for an extended period and likely not until 2021.

Relief for Limited Skadden Partnersin Investment Funds With TID US Portfolio Companies

As expected, the draft regulations codify the Committee’s established practice of viewing limited partners’ passive investments through fund structures as falling outside of its jurisdiction. Although FIRRMA foreshadowed this treatment, and the pilot program implemented it for critical technology transactions, CFIUS incorporated meaningful changes into these proposed regulations, including three in particular that both expand and narrow aspects of its application.

First, and as anticipated, CFIUS drafted these regulations to extend special treatment for funds investing in critical technology to include all TID U.S. Businesses.

Second, CFIUS adopted clarifying language from its previously published FAQ for the pilot program in order to codify the language. Specifically, CFIUS adopted definitions to better describe the types of “substantial decisionmaking” and other “involvement” that limited Skadden Partnerscould have in relation to an investment that would prevent the investor from enjoying relief from jurisdiction. Unsurprisingly, it appears that CFIUS intends to narrow the fund exception to apply to only truly passive investors. CFIUS construes “involvement” broadly, for example by including a limited partner’s right to provide input into a final decision, along with similar consultation rights, as activities that would render a limited partner a nonpassive investor for purposes of the fund structure. Note, though, that mere membership on a fund’s advisory board or similar committee does not necessarily trigger such involvement.

Third, while FIRRMA suggested that exemption from jurisdiction for certain foreign investments through funds be limited to U.S.-managed investment funds, CFIUS removed the explicit requirement for U.S. management in its proposed regulations. That said, the lone example that CFIUS provides highlights the treatment of a U.S.-managed investment fund, leaving some uncertainty surrounding non-U.S. managed funds.

Imposition of Filing Fees Is Further Delayed, but Penalties Are on Schedule

FIRRMA granted CFIUS the ability to impose a filing fee on a sliding scale not to exceed the lesser of 1 percent of the transaction value or $300,000 (adjusted annually for inflation). The draft regulations do not include a provision for such fees, with CFIUS indicating that regulations on fees will be published separately at a later date.

The draft regulations do, however, include new provisions for assessing civil penalties. For example, CFIUS is ready to codify penalties for failure to make any mandatory filings (up to $250,000 or the value of the transaction, whichever is greater) and retains its right to assess penalties for certain violations of mitigation agreements (up to $250,000 per violation or the value of the transaction, whichever is greater). CFIUS also proposes to implement a lower burden to assess a civil penalty (up to $250,000 per violation) for material misstatements or omissions in notices and declarations. All of these proposed provisions are clear reflections of CFIUS’ likely evolution toward a more aggressive civil penalty posture.7

In addition to monetary penalties, the draft regulations include provisions giving CFIUS other authorities to address noncompliance with mitigation agreements including, among others, the ability to require the noncompliant party to file notices of any covered transactions for a period of five years following the date of noncompliance. This further demonstrates that, in addition to expanding its jurisdiction to review new transactions, CFIUS is intent on ensuring compliance with its mitigation agreements.

Key Takeaways

- Voluntary Filings Are Still the Norm. At least for now, the vast majority of filings remain voluntary — but the draft regulations further illustrate those areas that have been and will remain acutely sensitive to CFIUS.

Both acquirers and U.S. businesses should consider CFIUS’ priorities outlined in the proposed regulations when considering whether or not to engage voluntarily with the Committee. FIRRMA not only expanded CFIUS’ jurisdiction to review additional types of transactions but also increased the Committee’s resources to pursue transactions not notified to the Committee. We have seen the Committee become increasingly aggressive in pursuing nonnotified transactions, and thus parties must carefully consider the risks associated with choosing to forgo filing, even when no mandatory requirement exists.

In other words, the regulations’ modest expansion of mandatory filings should by no means be taken as an indication that voluntary filings are unnecessary or that CFIUS will not continue to pursue nonnotified transactions. As has been the case for several years, CFIUS will continue to examine carefully a wide array of transactions based on the U.S. business, the foreign acquirer and the risks associated with the acquisition.

- Certain Noncontrolling Investments in TID U.S. Businesses Are Now Subject to CFIUS Jurisdiction. The proposed regulations provide definitions or factor-based tests for determining whether a U.S. business would be a TID U.S. Business. Except for critical technology investments subject to the CFIUS pilot program, these investments are subject to voluntary filing.

- CFIUS Interprets “Sensitive Information” Broadly. The draft regulations make clear that the Committee will continue to view a huge swath of data as sensitive, thus providing jurisdiction in many noncontrolling investments. Specifically, many types of data commonly collected by businesses — with the exception of basic credit card purchase data — will be considered sensitive when targeted to sensitive groups of people such as government employees or when involving the data of more than 1 million people generally. This confirms our understanding that personal data has become a critical national security issue for the Committee, and one that is relevant to a broad range of industries not traditionally thought of as raising national security considerations, including insurance, health care and marketing, among others.

- More Detailed Requirements Related to Critical Infrastructure Are Provided. The draft regulations provide extensive descriptions of the types of infrastructure that will be covered in a noncontrolling investment — to include significant information technology infrastructure — and the types of rights that would implicate CFIUS.

- There Are No Changes to the Current Mandatory Declaration Pilot Program Related to Critical Technology. As noted above, the current pilot program stays in place, but the draft regulations again make clear that the program — to the extent it remains — will automatically be updated once the Department of Commerce identifies specific “emerging and foundational technologies,” which we still expect to occur in the next four to six months, if not sooner in limited instances. We continue to expect that many key technologies such as robotics, autonomous vehicles and sensors, and artificial intelligence will be materially impacted by these changes.

- Mandatory Declarations May Be Less Useful Than They Would Appear, but Voluntary Declarations May Be Helpful. Although the regulations permit parties to file a declaration in cases where a filing is mandatory, in many cases it is preferable to skip the declaration and move directly to a filing. This is the case because — by definition — a mandatory declaration only involves a matter that has heightened sensitivity (either because of the technology involved or the government-controlled foreign person) and thus will often require the more robust process that a full filing provides.

By contrast, the proposed regulations’ creation of a voluntary declaration for TID US Businesses offers a greater likelihood — for a less sensitive foreign investor investing in a less sensitive business — of a more rapid resolution as compared to a full filing. We also expect that over time, CFIUS will become increasingly comfortable clearing less sensitive transactions through this new voluntary declaration path, especially with repeat filers. - Certain Transactions Involving the Purchase or Lease by, or a Concession to, a Foreign Person of Certain Real Estate Located in the U.S. Are Subject to CFIUS Jurisdiction. These transactions, which are subject to voluntary filing, confirm our past assessments of the circumstances under which physical proximity to a sensitive U.S. government site may create a national security concern.

- Regulations for the Treatment of Investment Funds Are Codified. As expected, CFIUS has codified its long-standing practice of not reviewing truly passive investments of limited Skadden Partnersthrough investment funds, but it will be important for a fund’s general partner to review its partnership agreements to ensure that the fund’s limited Skadden Partnersare effectively excluded from receiving material nonpublic technical information so that the limited Skadden Partnersare treated as passive investors by CFIUS.

- No Near-Term Relief Is Likely for “Excepted Countries.” Although the draft regulations establish a mechanism to “white list” friendly countries that would be excepted from mandatory filings, the process appears unlikely to produce quick results, and the draft regulations themselves recognize as much. That said, we expect that, regardless of whether there is a formal “white list” exception, the Committee will continue to view investors from the U.S.’ closest allies in a favorable light.

- Provisions Are Provided for Penalties and Damages. Consistent with CFIUS’ actions since FIRRMA’s passage if not before, CFIUS remains highly focused on compliance with mitigation agreements. It has long had several tools in its compliance toolbox, but the draft regulations’ civil penalty provisions make crystal clear that there will be very direct financial consequences for those parties that run awry of CFIUS’ requirements.

_______________

1 CFIUS has generally deemed “controlling” to be any equity ownership of (i) more than 9.9 percent or (ii) less than 9.9 percent if other indicia of control exist (e.g., the foreign investor can appoint even a single board member) beyond standard minority investment protections such as tag-along, drag-along and anti-dilution rights.

2 Importantly, consistent with long-standing CFIUS law and practice, all U.S. businesses remain subject to CFIUS jurisdiction if a foreign person obtains “control” over the business. The draft regulations do not change this central jurisdictional proposition.

3 Note that unlike under the pilot program for mandatory filings related to critical technology described further below, the Committee’s jurisdiction related to noncontrolling investments in critical technology from a voluntary filing perspective is not limited to certain industries identified by their North American Industry Classification System codes.

4 See our September 11, 2018, client alert “Tightened Restrictions on Technology Transfer Under the Export Control Reform Act.”

5 For a more complete description of the pilot program, see our October 11, 2018, client alert “CFIUS Pilot Program Expands Jurisdiction to Certain Noncontrolling Investments, Requires Mandatory Declarations for Some Critical Technology Investments.”

6 It is important to note that in control transactions, these “excepted investors” are not excepted and remain subject to CFIUS’ traditional jurisdiction.

7 An even more tangible example of CFIUS’ willingness to wield this new weapon is from 2018, when CFIUS imposed its first-ever fine for the violation of a mitigation agreement (note the $1 million fine).

This memorandum is provided by Grand Park Law Group, A.P.C. LLP and its affiliates for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended and should not be construed as legal advice. This memorandum is considered advertising under applicable state laws.